A.I. Disinformation: A Cautionary Tale

I will freely admit to being predisposed to an anti-AI chatbot stance. It’s Besos’ fault for making my first name synonymous with human-language-activated assistants. (No, I won’t turn on your lights, play D’Esposito or order your toilet paper for you.) But that’s not my only beef. A.I. has ruined search results. Google gets it wrong now, in ways it never did before. And the way humans use it makes it worse. Even the most basic web search – even with the AI function turned off – is now totally untrustworthy since the rise of Gemini, ChatGPT and other platforms that generate content based on large language learning models or natural language processing.

What’s the difference? Well, about 15 years or so ago, I could type a question or phrase into a search engine and someone else – anyone else – could type the same question or phrase into the same search engine from a different computer and get the same results. (It was on this basis that Dave Gorman’s Googlewhack Adventure was based – the idea being that there existed pairs of words which would return only one search result on the whole of the internet and that search could be repeated by other users… don’t remember it? Ask your parents or watch it on YouTube.)

The internet has grown so much in 20 years those days are certainly behind us. Pair any two seemingly unrelated words and the count of results will be at least in the thousands, hundreds of thousands if you don’t use “quotation marks” (limiting the results to instances where those words appear in the same order and proximity to each other as given between the symbols).

Social science researchers actually used to use the volume or popularity of search results as suggestive of social phenomena. You might have to turn off ‘personalised results’ or open a new tab in ‘incognito mode’, but colleagues of mine often opened their research presentations with a PowerPoint slide that showed the top 5 autocomplete options for a phrase to show what people commonly searched for. In 2013, the UN published an ad campaign based on the same idea, demonstrating widespread misogyny with Google’s autocomplete suggestions for “women should”. In another example, Google were accused of using their algorithm to manipulate the autocomplete suggestions (and consequent search results) for “Tories are…” or “Labour are…” in 2016.

In 2026, Large Language Learning Models (LLMs) make Google hit differently. It seems like user-input search terms are now assumed by the AI-driven search engine to be written as natural language rather than as a specific, targeted search. Google is no longer directing users to the information they’re seeking, it’s aggregating it and delivering it to you: telling you the answers rather than helping you find them.

While I’ve been on study leave in Autumn term 2025 I’ve been working on a topic I last researched in 2020. It’s not just that the muck on the internet has decreased in quality and I’m getting less relevant but more sponsored results now. It actually seems like Google is taking the keywords I’m looking for and guessing at a different way of interpreting my meaning. The search results that come back seem to get further from what I’m looking for the more I try to refine my search terms. It’s very annoying. If I was less sure of what I was looking for I’m pretty sure my research would end up on a completely different path.

And that’s the second part of the problem. Users have come to rely so heavily on Google and other search engines to find the answers to their questions that they trust the results implicitly without paying critical attention to the output.

Further, by putting the results in a natural language form – in sentences we can understand, as though written by someone we’re having a conversation with – they seem more trustworthy. We’re less likely to break down the constinuent parts of the sentences, to check the sources for each part of the statement, and so information gets linked that has no business being so. The results are totally inaccurate. It’s just plain wrong.

Let me give an example to show what I mean. I’m in the process of co-designing a module for teaching and learning at the university where I work. It’s about Visual Criminology, and one of the things I want my students to discuss is art made by prisoners. While I’m thinking about examples to suggest to my students, I recall a vague memory from long-ago reading that Charles Manson, head of the Manson Family (convicted of killing nine people in the late 1960s), made art in prison that was later sold or exchanged as ‘Murderabilia’. Given that this is the kind of thing my colleague and I will be asking students to find, select and critique as part of their Visual Criminology assessment, I searched for it on Google using the phrase “art by Charles Manson”.

Despite resisting Google’s repeated attempts to entice me with ‘AI mode’, the first part of my results look like this:

Figure 1: I Googled ‘Art by Charles Manson’, this screenshot shows the first part of the results

Figure 2: I Googled ‘Art by Charles Manson’, this screenshot shows the second part of the results

Figure 1 shows the AI Overview (not asked for) which includes the following text:

"Charles Manson created various forms of art... Types of Manson's Art... He painted portraits, including a notable one of himself as Silenus, held by the Smithsonian. [link] ...Where to See His Art... Smithsonian Institution: The Smithsonian American Art Museum holds his painting, "Charles Manson as Silenus". [link]"

The inclusion of those links suggest they give supporting evidence for the statements which say that Charles Manson, head of the ‘Manson Family’ cult, who murdered at least 9 people including actress Sharon Tate, painted a self-portrait called ‘Charles Manson as Silenus’ which is held by the Smithsonian Museum of American Art. Looks legit, right? The website to which those links refer appears lower down (see Figure 2), between YouTube and The Guardian links, and again as a regular search result after the AI suggestions section (the very bottom of Figure 2).

BUT. IF I check that link (and the word IF is doing A LOT of work in that sentence given what I’ve already said about how we use Google and other search engines now) the Smithsonian page tells me the painting with the title ‘Charles Manson as Silenus’ was painted by Grant Wood, not a self-portrait BY Manson as the summary said. Incidentally, if you recognise the name Grant Wood it’s because he was responsible for American Gothic (1930). According to Wikipedia, Wood grew up in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, USA.

Now, a brief interlude here. Universities have always warned students not to cite information they find on the internet without questioning it. The Skills Hub at the University of Sussex, for example, suggests these tools for critically evaluating sources including this sheet based on the CRAAP acronym. In lectures and seminars, instructors insist students trust only high-quality websites, preferably non-commercial, for factual information. (Which ones are appropriate to cite in an essay or assignment is a whole other question.) One of the ways we suggest making that distinction is the end of the web address AKA the domain extension. Wikipedia goes into some depth on this page but generally speaking, it goes something like…

.com = commercial, don’t trust it, don’t cite it.

For example, I pay to rent the domain alexaneale.com and it reflects only my opinions, not those of my employer. Like any .com website, including newspapers and news outlets, there’s no legal obligation for facts to be objectively verified to any particular standard, it’s not peer-reviewed, and it can be trusted only as far as any other source on the internet.

.org = organisations, use with caution.

Mainly not-for-profit but not exclusively. Could be a registered charity, could be a religious society (for examples), likely reflects that organisation’s political stance/values.

.gov = government, think critically about political and national agendas.

Again, you can count on the information on such a site to reflect that [present] government’s take on something but not an independent or unbiased view. This is where to go for policy documents, for example.

.ac.uk or .edu = educational, trust as a source of information (whether to cite it or not is another question).

I would never suggest that anyone should blindly accept anything they read anywhere, but as far as it’s possible to trust a website I would trust educational websites to be checked for accuracy by academics, educators or people whose job is concerned with knowledge, research and critical thinking. I would expect such a site to be conscious of the limits of it’s own claims to accuracy, to cite it’s sources and to invite users to make up their own minds.

The Smithsonian website – si.edu - under that logic, is to be trusted. However, it’s not the Smithsonian website that’s the problem – it’s the connection the AI is making AND it’s going further than that because Google AI is telling you precisely how to interpret the results. If that particular Smithsonian page was one in a long list of results for ‘art by Charles Manson’ without AI, it would probably be much further down the list than in this instance and so I would get more relevant results first. More than that, I wouldn’t be getting a generated summary that told me how to interpret the results, it would be simply listing websites as results of my search query and it would be up to me to look through the results for one that matched my intended context, and then to read the page to check the information and decide how accurate it might be. In this instance I would see the title and “(painting)” in the preview, think to myself ‘.edu, that’s a trustworthy site’ and then read the information on the page once I clicked the link to make sure Charles Manson had actually painted it and that it was the right Charles Manson.

Because that’s another part of the problem. It’s not just that the work called ‘Charles Manson as Silenus’ was painted by Grant Wood, NOT by Charles Manson as Google claims in it’s natural language result. It’s also not even OF Charles Manson. Not THAT Charles Manson anyway.

Grant Wood painted a work called ‘Charles Manson as Silenus’ in 1938. In that year, Charles ‘Manson Family’ Manson was 4 years old. The subject of this painting is a different Charles Manson. I don’t even need to see an image of the painting to know that it’s not the same person. The Charles Manson painted by Wood was the Secretary of the Chamber of Commerce of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in 1938. This is a satirical painting of a minor political figure, not a self-portrait by a famous convicted murderer and cult leader.

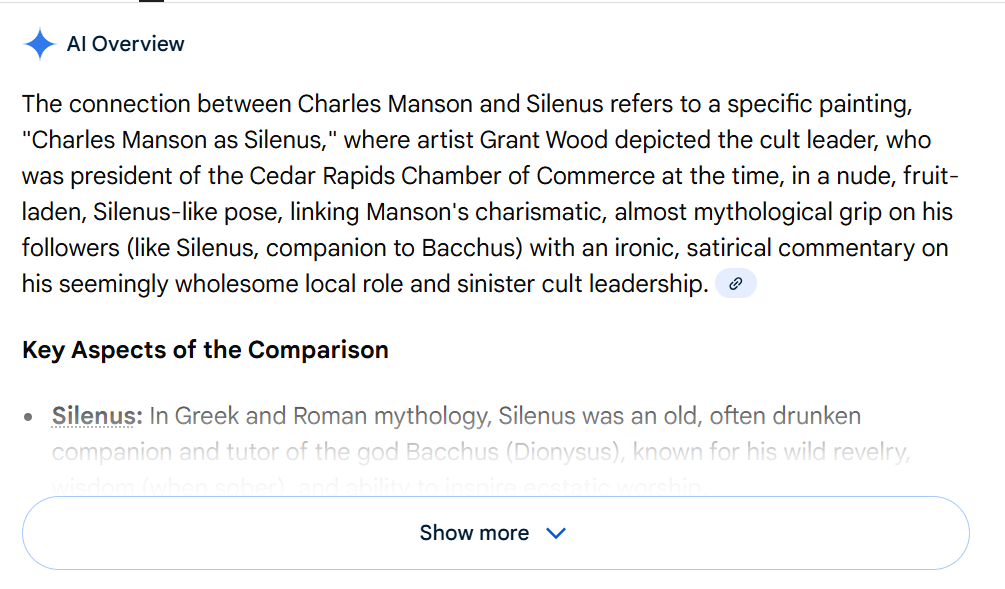

To make matters worse, when questioned further, Google tells me confidently that they are the same person.

Figure 3: Google result for ‘Charles Manson as Silenus’

According to the AI Overview in Figure 3 “Grant Wood depicted the cult leader, who was president of the Cedar Rapids Chamber of Commerce at the time…” No, he didn’t, and no, he wasn’t. Poor Grant Wood died in 1942 when the future cult leader was 8 years old so Grant Wood never depicted Charles Manson the cult leader. I’ve been unable to find a list of past presidents of Cedar Rapids Chamber of Commerce, so I can’t be absolutely certain, but I feel pretty confident in saying that Charles Manson the cult leader did not hold that position. If the painting was made in 1938, Manson the cult leader was 4 years old which doesn’t seem consistent with a position in that office.

And let’s not forget that we haven’t even seen the painting yet!

Going back to the above AI Overviews, particularly Figure 3, I think it’s important to note that they deploy intelligent language and include a link at the end as though citing a supporting source – both characteristics of a credible visual analysis. It sounds right. But it absolutely is not.

And the problem with LLMs is that information they give out that is uncritically adopted by time-poor humans then ends up in more online content, scraped by LLMs, repeating the lies. Before you know it, “Cult leader Charles Manson was president of the Cedar Rapids Chamber of Commerce aged 4” is an accepted fact. Or perhaps another explanation could be that the date on the Silenus painting is wrong, it was made in 1974 not 1934, and Manson was involved in the economic life of an Iowan city from his prison cell. Or maybe he had a little-known early career as a Cedar Rapids small business owner before he changed course and went into California cult-leading and inciting violence. (Unsupportive of those suggestions: Grant Wood’s death in 1942.)

Putting aside the implications of the promulgation of such falsehoods for the very nature of knowledge, the trustworthiness of facts found on the internet, let’s think about the implications of search engines getting things wrong for higher education.

Students who find themselves close to an assessment deadline and desperate for content (I’ve been there) might mistake statements like the above for fact, paraphrase them, put them in their essay, copy the given supporting citation. If they’re a bit more desperate, time-poor (for a variety of structural reasons) or lacking in confidence, they might simply copy and paste the whole statement.

And academics who find themselves close to a marking deadline and desperate to get through marking and feedback for another one of many papers (I’ve been there) might mistake those statements for a student’s own attempt at visual analysis. It would be easy to note the citation and give the student credit for making their comparisons and citing their sources.

Purely hypothetical scenarios but the implications are very real because we would both be wrong.

In conclusion, these are the key takeaways I think are important:

1. We’ve come to rely so heavily on search engines to find information that we haven’t questioned (or even noticed) the transition to AI-driven searching.

2. AI-driven searches tell you the answers rather than helping you find them.

3. AI-driven searches tell you those answers in sentences, as though we’re reading or hearing an authoratitive human voice, making them seem more trustworthy.

4. Trusting them means we’re less likely to click the links and check the information it claims to be aggregating by reading webpages (critically) for ourselves.

5. This is a mistake because the explicit answers are factually inaccurate and the implied connections misleading. AI-powered search engines get it wrong.

6. This has wide and significant implications for the future quality of education, teaching and learning, and knowledge more widely.

And 7. This is not Charles Manson of the Manson Family:

Charles Manson as Silenus by Grant Wood (1892-1942) from https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4666578

Post (c) Alexa Neale, 11 January 2026